A book discussing the history of witchcraft and witch trials

› Detail › A book discussing the history of witchcraft and witch trialsExhibit of the month 10 / 2016

A book from a specialized collection discussing the history of witchcraft and witch trials.

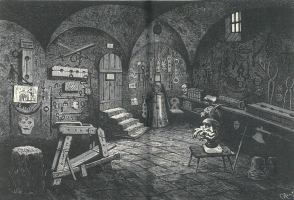

The text is divided into seven chapters accompanied by 20 illustrations of various types of torture and torture equipment. The title has enjoyed and continues to enjoy great interest among readers, especially in Germany, and has been published in many editions from the late 19th century to the present.

Our copy is among the less represented editions in the libraries of Central European countries; the Union Catalog of the Czech Republic does not list it in any library so far.

The original owner "Leo Schneider Oberleutensdorf" is noted on the front endpaper. According to the directory of the town of Litvínov from 1933, he was a merchant in Litvínov and lived at Freiheitsplatz (now 9. května street) No. 23. The book comes from the library of the City Museum in Litvínov.

Witch trials refer to secular and ecclesiastical criminal proceedings against witches and wizards (sorcerers). This is a historical phenomenon that lasted from the 15th to the 18th century, conducted by both Catholic and Protestant authorities.

The roots of the persecution of witches go deep into antiquity. The Code of Hammurabi in Babylon already dealt with the investigation of suspicions of witchcraft, including subsequent punishments. Similarly, the ancient Assyrians, Hittites, Persians, and Indians opposed witchcraft practices. In Roman law, which also became the basis of modern law, there was also the possibility of punishing a person practicing witchcraft (maleficium). The first prescribed punishment here was fire. Similarly, the Germans persecuted witchcraft, usually punishing by drowning. Particularly strict laws against witchcraft were issued by emperors Diocletian and, after the rise of Christianity, Theodosius I. The first person to be sentenced to death by a church court for heresy and witchcraft, despite many protests including from Pope Siricius, was Priscillianus, the bishop of Ávila, whose punishment was strangulation.

In the early Middle Ages, thanks to St. Boniface and St. Agobard, who considered witchcraft to be mere superstition and illusion, witch trials practically did not exist. The situation changed with contact with the Arab world after the Crusades. Punishments by burning for witchcraft began to appear in the legal codes of some countries as early as the 13th century. The first inquisitorial trials involving witches occurred in Germany after 1230. A truly mass and pan-European persecution occurred only at the end of the Middle Ages, especially at the end of the 15th century, reaching its peak in the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century. These so-called witch hunts spread in several waves across Europe, with the last wave occurring from 1750 in Canada, New England, and Mexico.

In 1486, the book Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) was published for the first time, a work by the Dominicans Kramer and Sprenger, who persecuted witches in northern Germany, with the support of Pope Innocent VIII. Interestingly, this book never represented the official teaching of the Catholic Church and was even condemned by the Inquisition in 1490 as unethical and even contrary to the Catholic understanding of contemporary demonology. Nevertheless, it became a widely used reference even in later times.

During the height of the witch hunts, no age or class was spared from persecution. Witchcraft often addressed political enmity, personal hatred, etc. In procedural law, denunciation replaced the indictment, and the accompanying proceedings were dominated by torture (among other influences from the aforementioned book The Hammer of Witches). Investigations were conducted according to schemes that did not allow for the evaluation of individual cases. Witch tests (with a needle, witch's bath) and means of favor (bribery) also came into play. The judicial process itself was thus completely distorted. Witchcraft was considered an extraordinary offense, and the defense of the accused was limited. In lighter cases, punishments included whipping, banishment, public ecclesiastical penance, and confiscation of property. The official sanction for the most serious witchcraft remains fire. Mass hysteria and crowd psychology often played a role in the trials.

By the mid-17th century, the frenzied hunts for witches began to wane, and the Enlightenment definitively put an end to the trials. In Austria, the persecution of witches was halted by Maria Theresa. The last trial in which a woman was accused of witchcraft took place in 1950 in the Belgian town of Turnhout. The witch was said to be Martha Minnen, who sought to refute her neighbors' slanders that she was a witch and demanded compensation for damages.

König, Bruno Emil, 1833-1902

Ausgeburten des Menschenwahns im Spiegel der Hexenprozesse und der Autodafés: eine Geschichte des After-und Aberglaubens bis auf die Gegenwart, historische Schandsäulen des Aberglaubens: ein Volksbuch. 206-215. Tausend.

Berlin-Friedenau: A. Bock, [ca 1935]. 734 s., [20] illustrations.